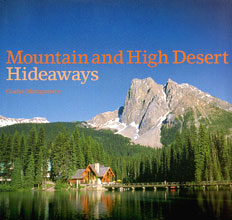

Mountain and High Desert Hideaways

Mountain and High Desert Hideaways

by Gladys Montgomery

Published by Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., NY.

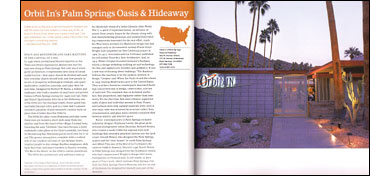

Orbit In’s Palm Springs Oasis & Hideaway

A little study of this plan is almost bound to impress one with the idea that here indeed is a new way of life, at least for those times when one craves a real rest. One gets interested, too, in the owner’s way of life in this new concept of a building venture. – Architectural Record, 1948

SPACE AGE MODERNISM AND SAKE MARTINIS IN THE CAPITAL OF COOL

In 1948, when Architectural Record reported on the Town and Desert Apartments, Modernism was the next new thing in Palm Springs. Not only was it avant-garde architecture, it represented new ideas of casual sophistication – how space should be divided and used, how everyday objects should look, and how people, in an era of prosperity, technological triumph, and space exploration, could live, entertain, and enjoy their leisure time. Designed by Herbert W. Burns, a builder and innkeeper who built a number of small inns and private homes in Palm Springs during the 1940s and ’50s, Town and Desert Apartments lives on as the Hideaway, one of the Orbit In’s two boutique hotels. Avant-garde has, inevitably, become retro, and in a town that’s a preservationist’s paradise of mid-twentieth-century style, no place does it better than the Orbit In.

The Orbit In’s nine-room Hideaway and nine-room Oasis inns are located a short walk away from one another and from the heart of the village. Cocktail hour, featuring the sake “Orbitinis” that have become a hotel trademark, takes place at the Oasis’s poolside, lava lamp lit-Boomerang Bar. Hideaway guests stroll over for it-or not. The groovy atmosphere, complete with a cocktail mix of rice crackers and nuts in ’50s Melmac bowls, inspires people to don vintage RayBan sunglasses, slick back their hair, and dance barefoot to Sinatra crooning “Fly Me to the Moon” on the Orbit’s custom soundtrack.

The Orbit In’s nine-room Hideaway and nine-room Oasis inns are located a short walk away from one another and from the heart of the village. Cocktail hour, featuring the sake “Orbitinis” that have become a hotel trademark, takes place at the Oasis’s poolside, lava lamp lit-Boomerang Bar. Hideaway guests stroll over for it-or not. The groovy atmosphere, complete with a cocktail mix of rice crackers and nuts in ’50s Melmac bowls, inspires people to don vintage RayBan sunglasses, slick back their hair, and dance barefoot to Sinatra crooning “Fly Me to the Moon” on the Orbit’s custom soundtrack.

The Orbit In’s architecture and ambience sum up the Modernist vision of a better lifestyle. After World War II, a spirit of experimentalism, an infusion of money from people drawn by the climate, along with new manufacturing processes and standardized building components innovated for the war effort, made the West fertile territory for Modernist design that had emerged early in the twentieth century. Frank Lloyd Wright had completed his first California project in 1909. In 1917, internationalist Le Corbusier published his influential Towards a New Architecture. And, in 1919, Walter Gropius founded Germany’s Bauhaus school, a design workshop unifying art and technology, the fine and applied arts, function and aesthetics. It was a new way of thinking about buildings. “The Bauhaus believes the machine to be the modern medium of design,” Gropius said. When the Nazis closed the school in 1933, leading Modernists came to the United States. They and their American counterparts innovated buildings unconventional in design, construction, and use of materials. The emphasis was on technical perfection, fine proportions, and regularity rather than symmetry. For the first time, thin steel columns supported walls of glass and roofs that seemed to float. Planes and surfaces were thin, natural materials were used in new ways, style was achieved by structure rather than ornamentation, and glass walls created a seamless flow between interior and exterior space.

Burns’ contemporaries in Palm Springs included industrial designer Raymond Loewy; the great architectural photographer Julius Shulman; Richard Neutra, who created a south California regional style with buildings that extended pinwheel fashion into the landscape; Donald Wexler, who designed the Palm Springs airport and the “steel homes” in north Palm Springs; and Albert Frey, one of the first of Le Corbusier’s disciples to build in America. Neutra’s 1946 Desert House in Palm Springs was designed for the Kaufmann family, who had commissioned Wright to design their home, Fallingwater, in Pennsylvania. It still stands, as does most of Frey’s work, which includes Palm Springs City Hall, the Palm Springs Desert Museum, and the second of the houses he designed for himself, now part of the museum.

Burns designed Town and Desert Apartments in 1947. The jagged L-shaped plan that stretches horizontally into the landscape included his home and office, and five rental units. A decade later, he designed the Oasis. Like the Hideaway, it was a collection of apartments around a pool, featuring strong horizontal lines and low-pitched roofs with deep overhangs. Burns achieved a flow between the indoor and outdoor spaces with floors that sit flat to the land, glass walls, natural materials, and a palette of desert hues.

The Orbit In’s owners, Oregon residents Christy Eugenis and Stan Amy, first saw the Oasis property while on vacation in Palm Springs. Eugenis, out Rollerblading, happened to see the “For Sale” sign in front of the rundown motel, which still had its vintage sign and name, the Village Manor. “All they’d ever done was paint and recarpet,” she said. “They hadn’t touched any of the original features – and that’s almost impossible to find.” They bought the Oasis in early 1999 and opened it in 2001, after nearly two years of renovations. In 2001, they bought the Hideaway, which then resembled a seedy set straight out of film noir; it opened in 2003. Under the guidance of architect Lance O’Donnell, of the firm O’Donnell and Escalante, who grew up in a Modernist house near Palm Springs, both properties received restorations that are ring-a-ding-ding on target, right down to the last Eames chair. “Most of my friends like to stay in small hotels, and I’ve always loved the ’50s because of the colors and the amoeba and geometric shapes, ” Eugenis said. “I spotted a trend.”

The Orbit In’s owners, Oregon residents Christy Eugenis and Stan Amy, first saw the Oasis property while on vacation in Palm Springs. Eugenis, out Rollerblading, happened to see the “For Sale” sign in front of the rundown motel, which still had its vintage sign and name, the Village Manor. “All they’d ever done was paint and recarpet,” she said. “They hadn’t touched any of the original features – and that’s almost impossible to find.” They bought the Oasis in early 1999 and opened it in 2001, after nearly two years of renovations. In 2001, they bought the Hideaway, which then resembled a seedy set straight out of film noir; it opened in 2003. Under the guidance of architect Lance O’Donnell, of the firm O’Donnell and Escalante, who grew up in a Modernist house near Palm Springs, both properties received restorations that are ring-a-ding-ding on target, right down to the last Eames chair. “Most of my friends like to stay in small hotels, and I’ve always loved the ’50s because of the colors and the amoeba and geometric shapes, ” Eugenis said. “I spotted a trend.”

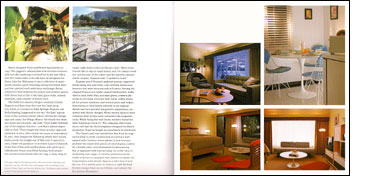

Eugenis and O’Donnell updated systems, improved landscaping and amenities, and carefully showcased features that were miraculously still intact. Among the original features are white enamel kitchenettes, baths tiled in pink, baby blue, and mint green, combed plywood accent walls, recessed wall clocks, soffits above all the picture windows, and vertical poles and ledges. Restoration in both hotels adhered to the original details and incorporated imaginative adaptations consistent with Burns’ designs. When electric heaters were removed, their niches were converted into magazine racks. While fixing the wall clocks, workers found the label ‘American Clock Co.’ The company, still in existence, still had the clock templates designed for Burns’ properties. Eugenis bought an assortment in aluminum.

The Oasis’s pool was moved four feet from its original location to allow construction of a privacy wall topped with Carolina cherry plants. A new terrazzo poolside bar inlaid with pieces of colored glass, crafted by a Seattle artist, and nicknamed the Boomerang Bar, is equipped with Internet plug-ins at the base of its glowing lava lamps. A colorful perforated metalshade structure is equipped with misters to render the temperature some twenty degrees cooler than it is in the sun. It’s a terrific place to relax in a 1966 Richard Schultz lounge chair, sip an Orbitini, and admire the San Jacinto Mountains.

For furnishings, Eugenis – a first-time hotel owner who’s had multiple careers as a real-estate agent, photo stylist, sportswear designer, and purveyor of vintage clothing – scoured secondhand stores, haunted estate sales, and tapped resale dealers in modern furnishings to find authentic furniture by Eero Saarinen, Charles and Ray Eames, Harry Bertoia, Jens Risom, Pierre Paulin, Marcel Breuer, and Isamu Noguchi, among others. A collection of Aimes Aire furniture surrounds the Hideaway’s pool. Modern pieces, like Blue Dot storage units, Jamaica bar stools by Spanish designer Pepe Cortez, and mid-century designs by Herman Miller and Knoll are also part of the mix. Ray Eames fabric introduced in 1999 was used for window treatments custom-made by a draper who had been working in Palm Springs for fifty years. New sea grass floor coverings complete the buildings’ original indoor-outdoor concept and provide an eye-soothing backdrop for furnishings.

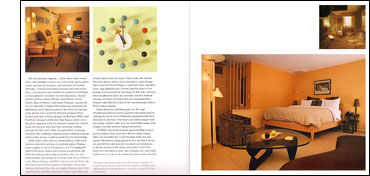

Both hotels offer suite accommodations with kitchenettes and either private or poolside patios. Vintage tunes supply in-room CD players, and TVs equipped with VCRs show classic and current movies from the Orbit In’s library. Each suite is themed with wit and individuality, and swings in neutrals with shots of Rose’s Lime, Rhum Orange, and Blue Curacao. At the Oasis, the Rat Pack Suite features photos of Frankie, Dean, and Sammy; Bertoia’s Den has an original Bertoia bird chair and ottoman; and the Leopard Lounge is just what one would expect from its name. There’s also the Atomic Paradise Room, where decor includes a 1958 Orange Slice chair by Pierre Paulin, a 1948 ball clock, and Blue Dot’s 1999 Modulicious cabinet; and the Albert Frey lounge, where photos of him hang on the wall, cabinets were inspired by those in his home, and the outdoor shower, privately enclosed behind a bougainvillea-draped wall, affords a view of the mountainside where Frey’s house stands.

Both hotels offer suite accommodations with kitchenettes and either private or poolside patios. Vintage tunes supply in-room CD players, and TVs equipped with VCRs show classic and current movies from the Orbit In’s library. Each suite is themed with wit and individuality, and swings in neutrals with shots of Rose’s Lime, Rhum Orange, and Blue Curacao. At the Oasis, the Rat Pack Suite features photos of Frankie, Dean, and Sammy; Bertoia’s Den has an original Bertoia bird chair and ottoman; and the Leopard Lounge is just what one would expect from its name. There’s also the Atomic Paradise Room, where decor includes a 1958 Orange Slice chair by Pierre Paulin, a 1948 ball clock, and Blue Dot’s 1999 Modulicious cabinet; and the Albert Frey lounge, where photos of him hang on the wall, cabinets were inspired by those in his home, and the outdoor shower, privately enclosed behind a bougainvillea-draped wall, affords a view of the mountainside where Frey’s house stands.

Julius Shulman’s photographs, for the 1948 Architectural Record article, guided restoration and furnishings decisions at the Hideaway. Appropriately, they decorate its interiors. The black and white images look uncannily similar to the way the hotel looks today: cool, elegant, and the furthest thing from kitsch.

“In Orbit” spa services leave guests feeling as pampered as Doris Day; Leave it to Beaver-style cruiser bikes are available for a spin through town; the San Jacinto Mountains tempt guests to lace up those sneakers and hit the trail; and the two pools are invitations to throw caution to the wind and perfect a tan. The Orbit In is the kind of place that reminds one that while California is a state of the union, it is also a state of mind.